© 2022 All Rights Reserved. Don’t distribute or repurpose this work with out written permission from the copyright holder(s).

Printed from https://www.damninteresting.com/hunting-for-kobyla/

On a January day in 1964, one thing exceptional occurred: Simon Wiesenthal took the afternoon off. He parked himself at a desk on the terrace of Tel Aviv’s Café Roval, absorbing the sunshine as if he wished to bottle it. The pal he’d come to satisfy was late, however Wiesenthal had no cause to complain.

He was nonetheless lounging along with his drink and his studying when the loudspeaker crackled to life over the murmur of café chatter. There was a cellphone name for Mr. Wiesenthal, the disembodied voice introduced.

When he rose to take the decision (it was the pal; he needed to cancel), a lot of Wiesenthal’s fellow café-goers stood up, too. Then they broke into applause. A spontaneous standing ovation might need startled the typical particular person, but it surely wasn’t the primary time crowds of strangers had risen to their toes in Simon Wiesenthal’s presence. Although when this occurred again residence in Vienna, it had typically been to spit at him.

Neither the love nor the hate fazed the 56-year-old although. Sure occupational hazards had been to be anticipated once you had been one of many world’s preeminent Nazi hunters.

Wiesenthal returned to his desk to gather his issues. When he acquired there, he discovered it occupied by three ladies who, he presumed, had pounced on the prime location. However the ladies weren’t there for his spot—they had been there for him.

“We should apologize for merely sitting down at your desk,” the primary lady instructed him in Polish. “However once we heard your identify on the loudspeaker we wished to speak to you. All three of us had been at Majdanek. So we thought we must always ask you. You should know what occurred to Kobyla?”

A lot for his time without work. Majdanek had been a focus camp also referred to as Lublin, and questions like these had just lately turn out to be the soundtrack of Wiesenthal’s life. After years of working below the radar, he’d just lately gained worldwide fame for his function (minimal although it was) within the seize of Adolf Eichmann, one of many Holocaust’s central architects. Wiesenthal’s subsequent ebook, I Chased Eichmann: A True Story, hadn’t harm his celeb standing, both. Because the ebook’s publication, Nazi victims had approached him in droves, begging him to assist uncover their former tormentors from the struggle that had ended nearly 20 years prior. Balding and middle-aged, Wiesenthal could not have appeared like a world crime fighter. However he had a necessary—and surprisingly uncommon—attribute that suited him to the work: the burning need to deliver the criminals of the Third Reich to justice.

Wiesenthal thought-about the three ladies. Their request was acquainted, however the identify they’d inquired about—Kobyla—was not. He knew that “kobyla” meant “mare” in Polish, however past that, he was at a loss.

“Forgive me,” the primary lady mentioned. “We all the time assume everyone should know who Kobyla was. We known as her that as a result of she was all the time kicking the ladies within the camp. Her actual identify was Hermine Braunsteiner… She was the worst of all of them.”

Wiesenthal sat again down as his new tablemates launched into tearful recollections of the jail camp guard who had terrorized the inmates of Majdanek. They instructed him she threw doomed kids onto vehicles destined for Majdanek’s fuel chambers. They instructed him she whipped a person so arduous that the kid hidden in his rucksack cried out. They instructed him she killed the kid on the spot.

“I imagine that in the event that they place shards on my eyes after I die, as is our customized, my useless eyes will nonetheless see that youngster’s face,” one of many ladies mentioned. Everybody’s drinks sat on the desk, forgotten.

“From each certainly one of my journeys I return residence with new names, the best way different folks deliver again a memento,” Wiesenthal instructed the trio as the nippiness of the evening crept over them. “From this journey it is going to be the identify of Hermine Braunsteiner.”

The obvious factor to do with a tip a few struggle felony who walked free would appear to be to go it alongside to the authorities. That choice scarcely crossed Wiesenthal’s thoughts. How occasions had modified. Within the early days of his Nazi-chasing profession, because the mud settled on World Struggle II, he’d counted the world’s strongest nations amongst his allies. He’d even taken a place with the U.S. Struggle Crimes Workplace, conducting interviews at displaced individuals camps to assemble tales—and accusations—from the folks there. Inside a couple of years although, his colleagues headed again to the States. When replacements arrived, they appeared way more involved in retaining tabs on the newer, flashier menace—the Soviets—than they had been in ferreting out enemies previous.

After years spent struggling to maintain his offshoot Jewish Documentation Heart afloat, Wiesenthal had all however given up on his marketing campaign for justice by 1954. However the 1960 Eichmann seize catapulted Wiesenthal into the highlight and reinvigorated his quest—in addition to his funds.

Most main gamers in world affairs continued to point out not more than a minimal curiosity in Wiesenthal’s work. However the consideration generated by Eichmann’s unmasking—and by his subsequent trial—proved to be a crash course within the energy of an unofficial supply of leverage: public opinion. Simply the earlier 12 months, in 1963, Wiesenthal had uncovered Karl Silberbauer, the police officer who had arrested Anne Frank and who nonetheless held a job in legislation enforcement. Although Silberbauer hadn’t been a high-ranking official throughout the struggle, his arrest made worldwide information, incomes time on American community information—regardless of having to share primetime with the Kennedy assasination. Wiesenthal took the lesson to coronary heart.

Wiesenthal knew folks can be repulsed by Braunsteiner’s wartime deeds. If he may repair the eyes of the world on the dramatic and disturbing story of the sadistic camp guard, he believed, he may strain these in energy to take motion. He wanted to show Hermine Braunsteiner. However first, he’d have to search out her.

Again in his workplace within the deep freeze of the Viennese winter, Wiesenthal set to work researching his goal. He discovered that she was a fellow Austrian and that she, like him, had hung out inside focus camps throughout the struggle, simply as the ladies on the café had claimed. Not like him, crucially, her presence there had been voluntary.

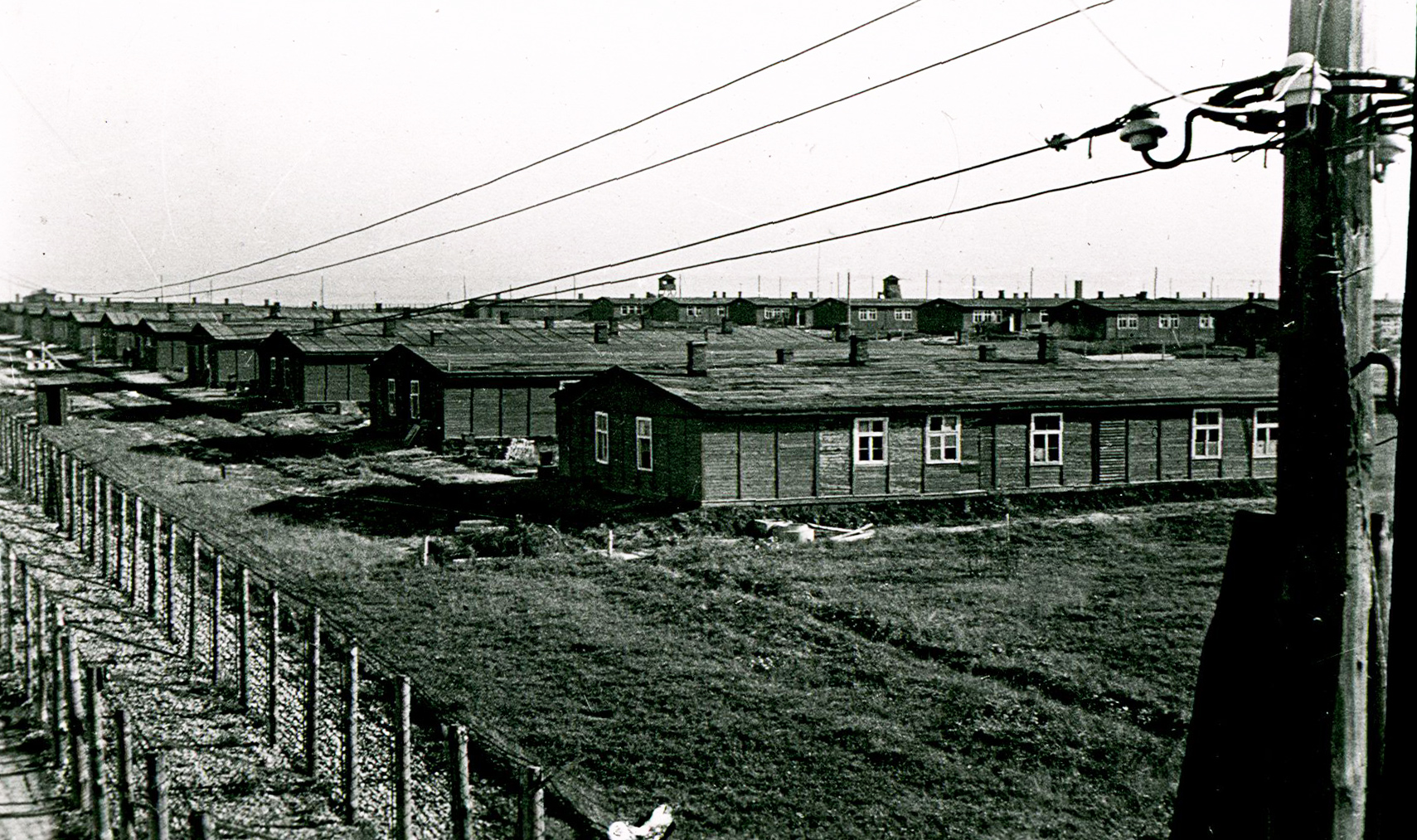

When Hermine Braunsteiner was transferred from Ravensbrück to Majdanek in 1942 to protect its new ladies’s part, the camp was solely a 12 months outdated. It had been the brainchild of SS chief Heinrich Himmler, who had ordered its development throughout a 1941 go to to Lublin. The camp was operational inside months, however Himmler’s imaginative and prescient for the location prolonged far past the struggle. In the future, he believed, Majdanek would function a clearinghouse the place compelled laborers might be conscripted to construct militarized and industrialized agricultural complexes all through jap Poland and the occupied Soviet Union. The consequence can be a group of hubs round which ethnic Germans may settle as they unfold out throughout their war-earned lebensraum (dwelling area).

Soviet prisoners of struggle had been the unfortunate winners of the preliminary Majdanek contracting job. Two thousand POWs started development within the fall of 1941. By February, overwork and publicity to the weather had left practically each certainly one of them useless. Officers swiftly conscripted Jews from an present camp in central Lublin to select up the slack.

The product of their labor was an impeccably designed hell with a mouthful of an official identify: Prisoner of Struggle Camp of the Waffen SS in Lublin. Wiesenthal, who had spent the second half of the struggle shuttling between camps, acknowledged the aesthetic. A former structure scholar, he had even taken it upon himself to sketch his prisons on scraps of paper throughout his internment. (The drawings, he figured, would depart behind a visible account of his expertise within the doubtless occasion that he wouldn’t survive lengthy sufficient to supply a verbal one.) Now, as he learn up on Majdanek, he doubtless had little hassle picturing its low, picket barracks set alongside pin-straight paths, nor the 2 layers of barbed wire fencing that separated them from the suburban city of Majdan-Tatarski, from which the camp had taken the nickname “Majdanek,” or “little Majdan.” The Majdanek guards’ space had featured a barber’s store and on line casino, whereas the prisoners’ space held sleeping quarters and cremation pyres. Close to Discipline 5, the ladies and kids’s part the place Hermine Braunsteiner would doubtless have spent most of her time, stood three fuel chambers.

By the tip of its less-than-three-year run, Majdanek proved deadly for roughly 80,000 of the 150,000 individuals who handed by way of its partitions. Prisoners died from overwork and malnutrition. They died from illness and harsh Polish winters. They died in clouds of poison fuel. When the wind blew towards city, the stench of dying drifted in with it. The property’s deadliest day got here on 03 November 1943, when SS and army males marched some 18,000 folks to an space simply exterior Majdanek’s partitions. To drown out the noise, camp administration blared music over the loudspeakers that stood tall all through the grounds. Hundreds of bullets later, all lay useless.

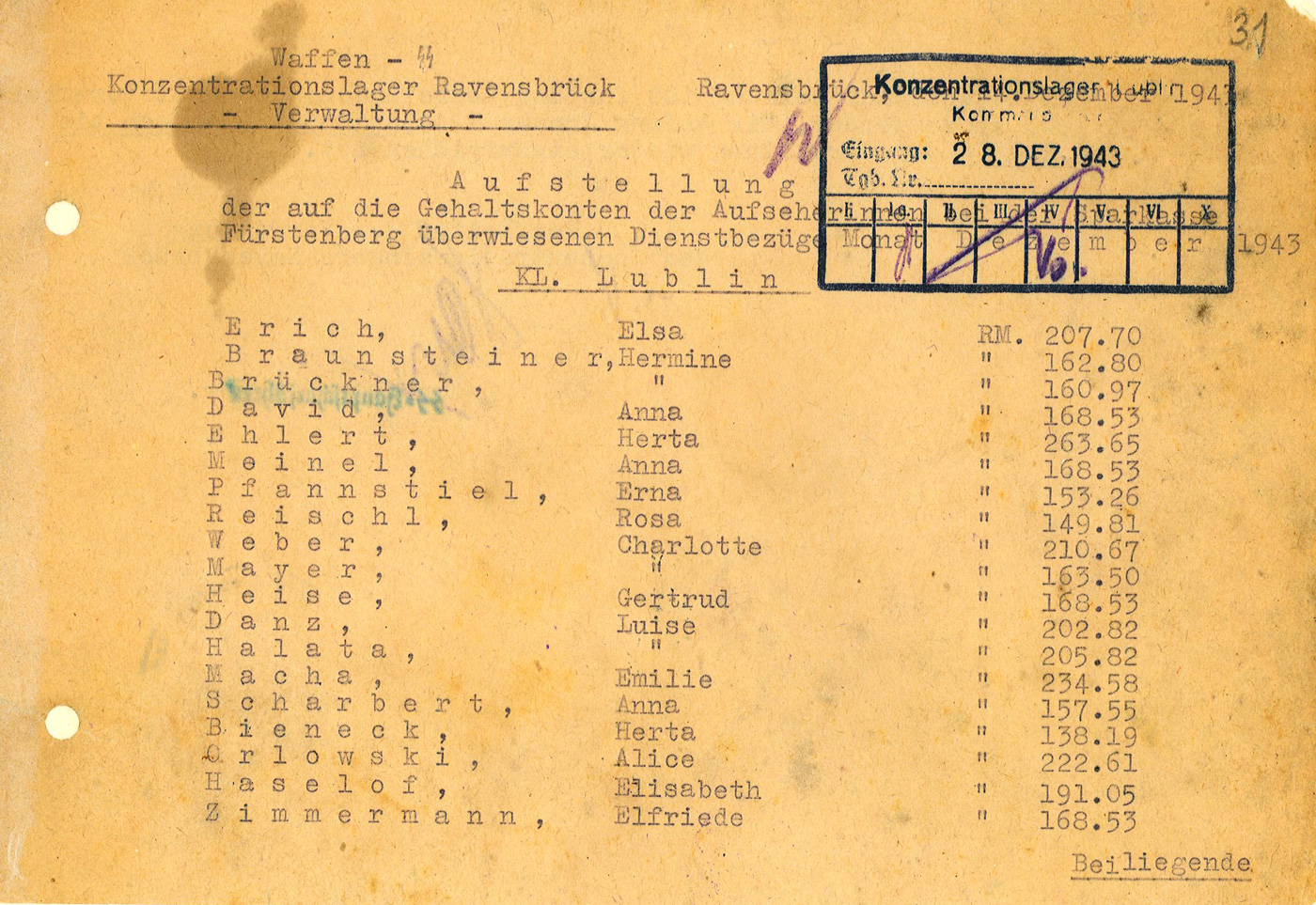

In January 1943, Braunsteiner acquired excellent news: She’d been promoted to Assistant Wardress. Maybe her superiors had been impressed along with her cruelty, which had sharpened since her arrival. She had dabbled in her justifiable share of prisoner abuse in her earlier place working as an overseer at Ravensbrück, however at Majdanek, she started to grasp the career.

Her assaults took many varieties, from lashings with a whip to assaults by the Deutscher Schäferhund (German Shepherd) that always loped alongside at her facet. Greater than something although, she grew to become identified for her penchant for utilizing her steel-toed boots as a weapon, kicking and trampling Majdanek prisoners who dared to step out of line—or just encountered her on the fallacious second. Her victims didn’t all the time survive. Braunsteiner went out of her manner, prisoners later claimed, to exert her energy and punish these below it. She even inserted herself into the choice course of, one witness recalled, throughout which prisoners had been sorted into those that would work and those that can be gassed. Whereas physicians separated the doomed from the spared, Braunsteiner took it upon herself to ship extra ladies to the previous group whom she felt, for no matter cause, the physicians had ignored.

Wiesenthal’s analysis into Nazi criminals and their killing grounds was by no means simple studying, however the historical past of Majdanek hit significantly near residence. With the assistance of the Polish Underground, Wiesenthal’s spouse Cyla had spent a lot of the struggle passing as Aryan in Nazi-occupied Europe. Although she survived, she encountered her justifiable share of shut calls. One such near-miss had come when she lived in Lublin, on the day officers had rounded up unregistered residents and despatched them to close by Majdanek. Had Cyla Wiesenthal not been in the back of the road when the registration workplace closed for the day—and had she not managed to flee later that evening—she could properly have come nose to nose with Hermine Braunsteiner.

Braunsteiner had managed to achieve her fame in file time, it appeared, as she was nowhere to be discovered when Soviet troops took Lublin in the summertime of 1944. Eighty of her former Majdanek coworkers had been swiftly convicted within the aftermath.

However Braunsteiner hadn’t managed to slide by way of the cracks completely. After a number of extra stacks of court docket data, Braunsteiner’s identify lastly surfaced on a doc from 1948. In accordance with the filings, the ex-guard was ultimately arrested in her native Austria. She’d been convicted, too, although the punishment had hardly been stiff. The sentence handed down by an Austrian court docket was a jail time period of simply three years. What’s extra, she’d solely been tried for her abuse of prisoners at Ravensbrück, the place she’d spent the early years of the struggle. Nobody had testified about Majdanek.

Wiesenthal lastly had some crumbs to comply with, however they had been stale at greatest. Even when she’d served her full time period, he calculated, Braunsteiner would have been out of jail for greater than a decade. The place may a convicted Nazi have gone subsequent? He had one guess: residence.

Conveniently for a sleuth on a price range, the home Braunsteiner grew up in shared its metropolis with Wiesenthal’s Vienna headquarters. Information on the Vienna registration workplace confirmed that she hadn’t lived there since 1946—two full years earlier than her arrest—however Wiesenthal had a hunch {that a} stroll round her outdated neighborhood can be definitely worth the journey.

Braunsteiner’s childhood residence sat greater than 40 kilometers exterior town middle. When Wiesenthal arrived, he discovered himself on a steep residential avenue close to the vineyards that jutted out from the sting of the leafy Vienna Woods. Braunsteiner herself is perhaps lengthy gone from this place, however with luck, he figured, a few of those that remained would keep in mind her. He started to knock on doorways. Finally, at 44 Kahlenberger Straße, he discovered somebody who didn’t appear greatly surprised by the unusual man on her doorstep inquiring a few long-gone neighbor. Fairly the opposite.

“After all I knew the lady,” the aged lady instructed Wiesenthal, ushering him inside. “What would you prefer to learn about her?”

“I’m involved in Fräulein Braunsteiner as a result of she was on trial,” he instructed her, not one to beat across the bush.

His bluntness didn’t appear to discourage his hostess. “Ah sure, the poor factor,” she mentioned. “I heard about it, in fact, and likewise that she was convicted. There have been every kind of stuff within the papers, about how she was mentioned to have handled the ladies within the camp. I can’t actually imagine it of her.”

It was true that Braunsteiner hadn’t appeared destined to be a killer. Quite the opposite, she’d as soon as dreamed of changing into a nurse. However her household hadn’t been properly off, the lady instructed Wiesenthal, and he or she was compelled to enter the workforce as a youngster whereas the world continued to limp by way of the Nice Despair.

There was little work to be present in Vienna, so after Hitler’s Anschluss introduced Austria below German management in 1938, Baunsteiner determined to attempt her luck in Berlin. There, within the coronary heart of the quickly increasing Nazi empire, she discovered a job at Heinkel Plane Works, a producer simply exterior town that will quickly turn out to be identified for the bombers it churned out for the German Luftwaffe. The work was regular however the compensation was meager. There have been higher prospects and pay, the 20-year-old found, at a brand new, ladies’s-only focus camp known as Ravensbrück that had opened close by. To a teenager brief on money, the gig should have gave the impression of a dream job. A 1944 newspaper commercial for Ravensbrück positions promised “good wages and free board, lodging and clothes.” Braunsteiner secured a place as an overseer. And at that work, she excelled.

As she embraced her new profession within the jail camp system, Braunsteiner was not often seen again in her outdated Vienna stomping grounds. In the course of the struggle, her aged neighbor heard from certainly one of Braunsteiner’s family that “Hermine was working as a jail warder in Germany and that she was properly.” Later, in 1943, “she turned up as soon as in Vienna,” however “The neighbors at first didn’t acknowledge her as a result of she was sporting a type of army uniform.”

The final time the lady had set eyes on Braunsteiner was simply after the struggle. “She got here to see me however she didn’t prefer it in Vienna,” the neighbor defined. “‘There’s nothing to eat right here,’ [Braunsteiner] mentioned. ‘I’ll go to my relations in Carinthia.’ And that’s the place she was arrested by the police. Maybe she is again in Carinthia, now that she’s served her sentence. She’s acquired loads of relations there.”

Earlier than Wiesenthal rose to depart, he requested for the names of Braunsteiner’s Carinthian family. The neighbor readily complied. Wiesenthal now had every little thing he’d come for.

However in Austria’s southern area of Carinthia, simply as in Vienna, Braunsteiner was nowhere to be discovered. It was time to take a extra strategic strategy. The search ought to resume in particular person, however this time, Wiesenthal would want a surrogate—somebody who believed within the work however wouldn’t stand out among the many members of the family of a identified Nazi—to go in his place. He knew simply the person for the job.

Within the afterglow of the Eichmann trial, Wiesenthal had earned loads of admirers—a few of whom wished to do greater than cheer him on. One such would-be volunteer was a strikingly good-looking 24-year-old whom Wiesenthal had nicknamed “Apollo.” Now, Wiesenthal summoned the younger man again to his workplace to make good on his phrase.

Along with his agent conscripted, Wiesenthal laid out his easy but dangerous plan: Apollo would journey to Carinthia, to the village the place Braunsteiner’s family had been mentioned to dwell. As soon as there, he would make contact below the pretext of a shared relative and discover out all he may. Nobody was to know his true identification, nor the true cause he was there.

Apollo set off and rented a room within the village. When he discovered the house belonging to members of Braunsteiner’s prolonged household, he gathered his braveness and knocked on the entrance door, armed solely with a tall story about widespread relations in Salzburg. The aged lady who answered was a lot much less inviting than the one Wiesenthal had met in Vienna. He have to be mistaken, she instructed him—she had no family in Salzburg. She moved to shut the door.

“Perhaps your husband is aware of one thing about it,” the beginner spy improvised. Reluctantly, she invited him in. Inside was a younger man who appeared extra inclined to welcome a stranger. After chatting for some time, the person invited Apollo to dinner.

Over the subsequent few days, Apollo cemented his place as a frequent houseguest, making dialog and becoming a member of the household for meals. He was cautious to maneuver slowly, lest he present his hand. It wasn’t till his fourth go to that he determined to check the waters and lead the dialog towards Hermine Braunsteiner. He instructed the assembled group a few fictitious uncle who, Apollo lamented, had been wrongly convicted for his involvement within the struggle.

“The identical factor occurred to a girl relative of mine,” replied certainly one of his hosts. “She was sentenced simply because as a guard in jail she’d slapped the faces of some Gypsy ladies. However fortunately that’s over. 5 years in the past she married an American and is now dwelling in Halifax in Canada.” No surprise she’d been so arduous to search out.

Later, Apollo took a stroll with the younger acquaintance with whom he’d shared his first meal and determined to press his luck. “After all you’ll go and see your relative in Canada sometime?” he requested casually as they strolled.

“That will be good, however I’m afraid it could value some huge cash,” his new pal replied.

“Canada has all the time been my dream,” Apollo provided rapidly, retaining the dialog going. “Splendidly wild and untouched surroundings. Perhaps I’ll have saved up sufficient in a 12 months or two to go there. In that case, I’d lookup your relative and provides her your good needs.”

In response, his acquaintance provided one final important perception: “Her identify’s Ryan now.”

With Apollo’s important data in hand, Wiesenthal reached out to an acquaintance in Toronto and recruited him to do some digging on Braunsteiner’s Canadian whereabouts. In simply three weeks, the pal despatched an replace. There was good and dangerous information, he wrote: He’d discovered her, however she “now not lives in Halifax. She has moved to the USA and lives in Maspeth, Queens, N.Y.”

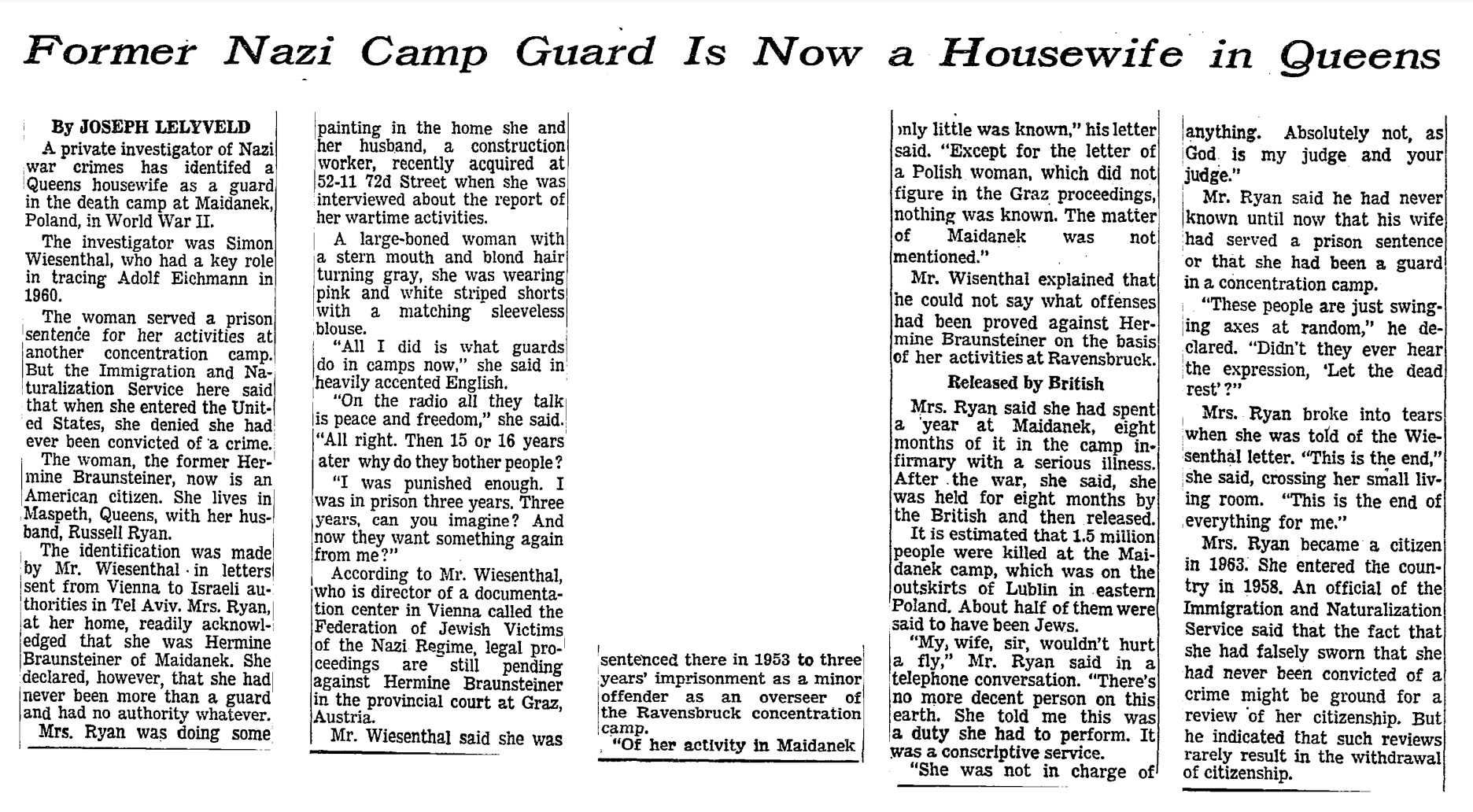

This improvement put a little bit of a wrinkle in Wiesenthal’s plan. In America, Wiesenthal knew that Nazi struggle criminals slept simple. Not one former Nazi dwelling as a U.S. resident had been extradited by the federal government within the practically 20 years for the reason that struggle’s finish. However each new American additionally needed to affirm that they’d by no means, “in the USA or in every other place…been arrested, charged, convicted, fined, or imprisoned for breaking or violating any legislation.” If Braunsteiner had certainly obtained U.S. citizenship, she had lied on her software to get it by conveniently forgetting to say her three-year stint in an Austrian jail twenty years earlier than.

However tips on how to get to her? Wiesenthal may try and contact the American authorities, in fact, however their obvious disinterest within the Nazis dwelling amongst them made that choice distinctly unappealing. As an alternative, he determined, he would flip to his beforehand tried and true ally: publicity.

Wiesenthal knew his justifiable share of journalists who may assist flip his search right into a story. After some consideration, he selected Clyde Farnsworth, a Vienna correspondent for The New York Instances who’d just lately profiled Wiesenthal for The New York Instances Journal. There was a Nazi dwelling in his paper’s again yard, Wiesenthal instructed the reporter. Certainly, his stateside colleagues would wish to take a more in-depth look? Wiesenthal wrote up an in depth account of what he knew and requested Farnsworth to go it alongside to the precise particular person within the New York newsroom. Farnsworth obliged.

However the task failed to achieve any of the paper’s high reporters, touchdown as an alternative on the desk of Joseph Lelyveld, a freshman reporter who had solely just lately been promoted from trundling backwards and forwards on the subway fetching experiences from the Climate Bureau.

It was a Friday morning in June 1964 when Lelyveld set out for the working-class neighborhood of Maspeth, and he had a sense it was going to be a protracted day. His orders had been so simple as they had been daunting: He was to find one Mrs. Ryan and inquire about her previous. As he compiled a listing of addresses, the younger reporter couldn’t assist however discover that there have been a lot of Mrs. Ryans dwelling in Maspeth. Having no explicit concept the place to start, he merely began ringing doorbells. The primary Mrs. Ryan wasn’t the one Lelyveld was on the lookout for, however, to his shock, she nodded when he requested whether or not she knew of a unique one that shared her identify and “who had come pretty just lately from Austria, presumably with a German accent.” She pointed the younger reporter to 72nd Avenue.

Little question amazed by his good luck, Lelyveld set out for the tackle Mrs. Ryan No. 1 had indicated. There, he discovered a modest, shingled home with stone steps resulting in the entrance door. He knocked. A girl opened the door. She was tall and middle-aged, her blonde hair coiled in curlers. Clearly, she hadn’t been anticipating company. With a paintbrush clutched in her hand, she appeared like every other homemaker benefiting from a summer season day to deal with an overdue DIY mission.

“Mrs. Ryan,” Lelyveld mentioned, “I must ask you about your time in Poland, and the Majdanek camp, throughout the struggle.” The shocked housewife stared again at him. May this harmless-looking lady in pink-and-white-striped shorts actually be the sadistic Nazi Wiesenthal’s tip described?

Then she broke. “Oh my God, I knew this may occur,” mentioned the lady, her eyes watering. “You’ve come.”

Inside, the previous Nazi focus camp guard sat with the son of a rabbi in her “tidy lounge” and protested the record of accusations from Wiesenthal. She’d been no worse than anybody else, she instructed Lelyveld, and in addition to, she argued, “I used to be punished sufficient. I used to be in jail three years. Three years, are you able to think about?”

Upon his return to The New York Instances constructing on West forty second Avenue that evening, Lelyveld’s cellphone rang. It was Russell Ryan, Hermine’s husband. The center-aged electrician wasn’t completely satisfied. “My spouse, sir, wouldn’t harm a fly,” he instructed Lelyveld. “There’s no extra first rate particular person on this earth.” Mr. Ryan appeared to be amongst these simply now discovering the character of his spouse’s wartime alter ego, however these revelations hadn’t shaken his marital devotion. “These persons are simply swinging axes at random,” he instructed Lelyveld. “Didn’t they ever hear the expression, ‘Let the useless relaxation’?”

Although Russell Ryan didn’t achieve killing the story, he did handle to provide Lelyveld pause. The reporter frightened that he hadn’t spent sufficient time corroborating Wiesenthal’s claims. The article, initially slated for the entrance web page, finally went to print a number of days later, wedged right into a spot on web page 10.

Regardless of its demotion from the entrance web page, Lelyveld’s story made an instantaneous splash. A Nazi in America? Residing peacefully and undetected within the nation’s most well-known metropolis, no much less? Little question there have been many who assumed motion can be swift. However it quickly grew to become clear that discovering Hermine Braunsteiner wasn’t the identical factor as catching her. It was time to name within the bureaucrats.

Twenty years and a number of other thousand miles faraway from the post-war tribunals overseen by the Allied powers, the U.S. authorized code contained no legal guidelines that lined Braunsteiner’s actions. Heinous because the allegations is perhaps, the U.S. authorities had no method to sentence her in an American court docket for her crimes, which had been dedicated neither on American soil nor as an American citizen. If Europe wished to carry the ex-Nazi accountable, that was Europe’s enterprise. The one factor the U.S. may do can be to kick her in another country, and even that seemingly simple matter was sneakily complicated. Braunsteiner wasn’t a fugitive or an undocumented alien. Nobody—save for Simon Wiesenthal—was on the hunt for her. After which there was the minor matter of her American citizenship.

To deport an American Nazi can be an unprecedented transfer, one that will require the efforts and coordination of two separate federal entities. Having no jurisdiction over the lives of residents, the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service had no hope of delivery Braunsteiner in another country so long as she may cling to her protected standing. It could be obligatory, due to this fact, to deprive her of this authorized power discipline earlier than the rest might be accomplished. The duty of eradicating her citizenship, Herculean in itself, fell to the Division of Justice.

It took 4 full years earlier than the DOJ determined it had sufficient proof, partly due to witnesses obtained with assist from Simon Wiesenthal, to show that Braunsteiner had lied on her citizenship papers when she claimed to haven’t any prior arrests. “Had the defendant disclosed the true information of her conviction, she would have been barred from lawful admission into the USA,” the Justice Division introduced in 1968 because the trial kicked off in Brooklyn federal court docket.

Because the court docket case started, TV digicam crews surrounded the Ryans’ home. However the trial itself, which dragged on for years and wasn’t open to the general public, sustained little consideration. The New York Instances printed only one article in regards to the proceedings, whereas Joseph Lelyveld, who first broke the story, pursued a reporting profession that took him abroad as a international correspondent. Wiesenthal, in the meantime, was busy in Vienna, publishing a number of books and choosing fights with high-ranking members of the Austrian authorities, a number of of whom he accused of being former members of the SS.

To an outdoor observer, the case in opposition to Braunsteiner could have appeared open and shut, however the court docket battle raged for 3 years earlier than the defendant made the shocking determination to surrender her U.S. citizenship—with out admitting guilt to any wrongdoing. It was now 1971. Braunsteiner, now not a citizen, was lastly below the jurisdiction of INS.

The INS try and deport the New York Nazi fell to 2 males. Main the cost was Vincent Schiano, chief trial legal professional and a virtually 20-year INS veteran. Schiano was a “flamboyant dresser” who as soon as sported an “open-necked pink shirt and blue polka dot swimsuit” to a media interview. “He seems to be extra like a Mafia numbers runner,” concluded one reporter, “than the INS’s…high lawyer.” Schiano’s quantity two, chief investigator Anthony DeVito, was a fiery chain smoker and longtime INS investigator who had been one of many first folks to set foot inside a newly liberated Dachau as a member of the Air Power and who’d discovered German from his spouse, a girl he’d met within the aftermath of the struggle.

Each Schiano and DeVito acknowledged how essential the case was. If they may persuade the choose to rule in opposition to Hermine Braunsteiner, they’d be making historical past—to not point out ridding the nation of a struggle felony. However Schiano and DeVito’s superiors didn’t appear to share the sense of urgency, and it didn’t take lengthy for the 2 males to develop a “humorous feeling” (as Schiano later put it) that not everybody was as desperate to see Braunsteiner deported as they had been.

It began with resourcing. As an skilled INS prosecutor, Schiano was accustomed to getting no matter requested for whereas on the job. This time round, regardless of the high-profile nature of the case, he discovered himself barely scraping by. When he arrived on the 14th-floor workplace that had been offered for him and DeVito in downtown New York Metropolis, Schiano discovered a stuffy, cramped area. It was clearly not a room meant to carry two grown males, not to mention function headquarters to an anti-Nazi operation. The workplace additionally appeared to be lacking a phone. The one manner they’d have the ability to make a name, he realized, can be to make use of the shared receiver within the hall or shell out cash for the payphone down the corridor.

Undeterred, Schiano and DeVito set to work. And stayed at work, clocking lengthy hours by way of the weekends hunched over their metal desks. However between the marathon hours spent interviewing witnesses and retaining cautious, handwritten notes, the 2 males continued to wonder if the remainder of the INS was behind them—and even on their facet. DeVito’s suspicions had been infected when a locked file cupboard was damaged into in a single day. Later, when witnesses touring from Europe to testify in opposition to Braunsteiner arrived in New York, they found that the modest stipends they’d been promised had been mysteriously tied up. The cash went unpaid for weeks whereas DeVito circled the INS workplace gathering donations to cowl room and board.

No matter Schiano feared about what was occurring behind the scenes on the INS, he knew that after he went to trial, he’d have entry to the identical weapon Wiesenthal had discovered to wield so deftly: public consideration. After months of feverish work, the chief legal professional was able to make his case. The litigation in opposition to Braunsteiner wasn’t felony, so she wouldn’t be arrested, not to mention shackled on the middle of the courtroom. However she can be uncovered, and Schiano had cause to imagine folks would take discover. On 07 February 1972, the trial to deport Hermine Braunsteiner started, and for the primary time since she was initially found again in 1964, the 53-year-old Nazi focus camp administrator turned American housewife grew to become main information.

It had been practically eight years since Braunsteiner first made headlines, and People rediscovering her story had been confronted with a slew of surprising allegations. Aaron Kaufman, a 71-year-old survivor of eight separate focus camps, testified that he had seen Braunsteiner whip 5 ladies and kids to dying at Majdanek. One other former inmate claimed to have seen Braunsteiner assist load kids onto vehicles certain for fuel chambers. A dentist who had spent greater than a 12 months at Majdanek flew from Warsaw to New York to inform the court docket, simply because the three ladies had instructed Wiesenthal in Tel Aviv, that Braunsteiner had been so infamous for kicking prisoners that she earned a nickname at camp: Kobyla, or “the mare” within the lady’s native Polish. When she was requested to determine the accused, the 51-year-old witness had no hassle. “The second I walked in, I acknowledged her,” she mentioned.

“Simple to say,” Braunsteiner muttered to her husband, seated beside her.

Simon Wiesenthal little question saved tabs on the trial, which acquired copious protection from The New York Instances and different shops, however by no means attended a session himself. He had his fingers full throughout the Atlantic, the place he continued to make public accusations and strain governments to prosecute ex-Nazis.

For her half, Braunsteiner continued to current herself as each helpless and with out remorse. Court docket sketches present a girl in huge lapels and a flat expression, her mouth sloped down on the edges, eyes narrowed, and eyebrows arched. She did ultimately acknowledge that she knew Majdanek was an “extermination camp,” and mentioned she’d been “shocked and appalled” by what went on there. However finally, Braunsteiner stood by her lack of culpability. “It was not in my energy to do something,” she insisted. “I used to be too little.”

Requested whether or not she had accomplished something throughout her time on the camps that she was ashamed of, the defendant answered merely, “No.”

Many who heard in regards to the trial had been, unsurprisingly, outraged. Demonstrators gathered on the streets of Queens to protest the truth that Braunsteiner was nonetheless free to dwell her life as a New Yorker. One significantly passionate activist misinterpret the Ryans’ residence tackle and threw a firebomb by way of the window of a home six blocks away. However public response to the courtroom revelations was hardly as unanimous as might need been anticipated. “A few of these persons are actual nuts,” mentioned a Maspeth resident. She wasn’t speaking about Braunsteiner.

For essentially the most half, Braunsteiner’s alleged secret previous didn’t a lot misery her neighbors. In defending her, they had been fast to level out how properly she exemplified the character of Maspeth, a protected, middle-class group populated primarily by Poles, Lithuanians, Germans, and Irish. “I discover it not possible to imagine the accusations in opposition to her,” one neighbor instructed a reporter. “No person may have modified that a lot.” One other summed up the idea for the neighborhood’s shared disbelief extra straight: “She’s all the time working round the home. You by no means noticed such an individual for retaining the home clear.”

As time went on, Braunsteiner and her supporters had increasingly more cause to really feel hopeful. The trial, which had at first made headlines, quickly stalled. Between the autumn of 1972 and spring of 1973, the court docket held precisely zero classes. Maybe on this struggle of attrition, she may merely run out the clock. However in March, a brand new bomb dropped, courtesy of the Federal Republic of Germany.

After years of conducting its personal investigations, the West German authorities had concluded that it could very very similar to to prosecute Braunsteiner itself. So, on 22 March 1973, the Minister of Justice dispatched a 300-page software for extradition. As soon as the request was submitted, the query of whether or not the West Germans truly had the precise to place Braunsteiner on trial briefly grew to become a matter of some debate. Braunsteiner, in fact, was Austrian, not German. What’s extra, Majdanek, the camp at which she had spent essentially the most time, had been in Poland, a rustic which, by the way, had filed its personal extradition request. On this query, Braunsteiner and the West German authorities had been in settlement. Fearing harsher punishment in Poland, she thought-about German justice the lesser of two evils. Fortunately for her, the West German authorities was agency, and the American authorities concurred. She had been a supervisor at a German focus camp, in any case, and had acted “within the train of German sovereignty.” If she was ordered out of the U.S., Braunsteiner now knew that West Germany can be her vacation spot.

The stakes for the previous guard had simply gotten an entire lot increased. In response to the extradition request—and for the primary time since her discovery—Braunsteiner was positioned in custody. She spent the evening behind bars at Rikers Island. At her arraignment the subsequent day, she complained that she’d been compelled to sleep alongside prostitutes. (Alas, how the prostitutes felt about having to spend the evening with an alleged Nazi torturer has been misplaced to historical past.)

Sleeping preparations would quickly be the least of Braunsteiner’s worries. Simply two months after the West German extradition request, the trial’s chief choose handed down his ruling. On 02 Might 1973, the court docket declared that Hermine Braunsteiner’s life in America was over. Almost 10 years after being found, and nearly 30 years after she left Majdanek, Hermine Ryan, née Braunsteiner would return to Europe to reply for what she’d accomplished.

On 08 August 1973, now 53 years outdated, Hermine Braunsteiner Ryan was led from her cell within the Nassau County Jail to a small holding room at Kennedy Worldwide Airport. Holding a Coca-Cola and a field of knitting provides, she boarded the 6:45 p.m. Lufthansa flight certain for Düsseldorf, West Germany.

She wasn’t going to face the court docket instantly. Because it occurred, Braunsteiner was not the one former Majdanek guard the Germans had tracked down, and the authorities had determined to reunite Braunsteiner along with her former coworkers in a single trial. Braunsteiner languished in a Cologne jail for 2 years earlier than costs had been filed. When she lastly hurried into the Düsseldorf courthouse in 1975 for her necessary office reunion, face hidden behind a newspaper and brief hair lined with a white knit cap, she joined 5 different ladies and 9 males, all eliminated a minimum of 30 years from their struggle days. “They appeared,” noticed a columnist for The New York Instances reporting on the trial, “like all row of aged, modestly dressed passengers on a streetcar.” Of the 15 folks on trial, Braunsteiner was the one one who had not made bail, and remained behind bars.

If Wiesenthal had initially been relieved to see Braunsteiner face justice, his impression of the matter quickly soured. “What’s happening in Düsseldorf is a circus,” he instructed one reporter. He had a degree. Legal professionals for the protection had been ruthless, ripping into the witnesses—all Majdanek survivors, a lot of them aged—who had been known as to testify. (One legal professional demanded {that a} former camp inmate who recounted being compelled to deliver canisters of poisoned fuel to the fuel chambers be charged as an confederate.) The trial dragged on this fashion for years.

Exterior of the courtroom although, there was little vitriol. Regardless of the horror of its topic, the trial was sluggish, slowed down by mundane procedural debates, stalling protection attorneys, and witnesses who had little reminiscence of the issues they’d seen or accomplished so a few years earlier than. German newspapers hardly lined the proceedings, and a few politicians went as far as to name for amnesty. For her half, Braunsteiner was once more dwelling as a free lady inside a 12 months of the trial’s begin. She returned every evening to not a jail cell however to a small residence close to the courthouse, due to the $17,000 (about $51,000 in 2021 {dollars}) raised for her bail by sympathetic teams, together with the New-York-based Hermine Braunsteiner Ryan Basis.

By 1981, the trial had spanned 474 classes, featured 254 witnesses, and lasted 5 and a half years (nearly twice so long as the Majdanek camp was in operation), making it the longest and costliest in German historical past. Throughout that point, two of Braunsteiner’s protection attorneys had died, as had a minimum of certainly one of her fellow defendants and a number of other witnesses. (Simon Wiesenthal’s 1975 quip that “Dying is quicker than German justice” appeared prescient.)

Of their closing assertion, Braunsteiner’s protection attorneys centered on technicalities moderately than their consumer’s precise innocence. Her extradition, they argued, had been unlawful. Plus, she was an Austrian, not a West German, so how may she be held accountable to a international authorities? Moreover, they contested, she’d already served time for her alleged misdeeds again in Austria within the aftermath of the struggle. With that, the trial got here, in the end, to an finish.

On 30 June 1981, the ex-guard identified for her whip and her steel-toed boots filed into the courtroom for the ultimate time. It had been nearly a decade since she had boarded the airplane certain for West Germany and greater than 15 years since a younger Joseph Lelyveld—now simply 5 years away from profitable a Pulitzer Prize—had knocked on her entrance door in Queens. It had been practically 20 years since Simon Wiesenthal had tried to take the afternoon off at a café in Tel Aviv. Braunsteiner was now 61 years outdated, her hair metal grey. Her husband Russell, who had adopted her to West Germany in 1977, sat within the guests’ gallery.

With him had been a smattering of different onlookers, some pleasant, some hostile. It was hardly a big or rambunctious crowd. Because the assembled spectators peered down into the courtroom, they may see solely the backs of the defendants who sat quietly and confronted ahead as they awaited their destiny. An eerie calm hung over the room. When the choose entered the room, one journalist famous, he was the one one who appeared uneasy.

All eyes mounted on him as he learn out the decision. Hermine Braunsteiner, who had been accused of enjoying a job within the deaths of greater than 1,000 ladies and kids, was responsible of precisely two of them, he introduced. After a lot time, it was all of the proof may show. She would pay by spending the rest of her life in jail. Of the 9 remaining defendants (seven of whom had been discovered responsible), she alone acquired a life sentence.”Scandal!” shouted one man within the public gallery, outraged by the leniency. “You might have discovered nothing, completely nothing!” An emotional prosecutor may muster solely shock. “Shocking,” he mentioned. “Very shocking.”

These on the opposite facet expressed equal distaste. “American Jews demanded these trials, and that is what occurred,” Russell Ryan concluded bitterly.

Braunsteiner’s second stint as a convict lasted lower than 15 years, much less time than elapsed between Joseph Lelyveld’s fateful story and the German trial’s conclusion. Launched as a result of sick well being attributable to her diabetes in 1996, she spent her last three years in a German nursing residence alongside her ever-loyal husband. She died in 1999 at age 79.

Moderately than opening the floodgates for struggle crimes extradition from the U.S., Hermine Braunsteiner proved to be one of many few ex-Nazis—and the one feminine one—ever faraway from the nation. Fewer than 70 identified Nazis have been deported, extradited, or left voluntarily since. What number of extra have lived their lives undetected is much less clear.

After Braunsteiner’s extradition case wrapped up, each Schiano, the chief INS legal professional, and DeVito, the chief investigator, publicly accused the INS of dragging its toes and avoiding Nazi prosecutions. Each males left the company, in 1972 and 1973, respectively. In 1974, Congresswoman Elizabeth Holtzman publicly accused the federal authorities of neglecting the seek for Nazis within the U.S., and in 1977, DeVito and Schiano had been lastly known as to testify earlier than Congress. The Workplace of Particular Investigations, the federal government’s first official Nazi looking company, wasn’t established till 1981.

As for the person who introduced Hermine Braunsteiner her undesirable fame, Simon Wiesenthal continued to make the headlines—and the enemies that got here with them—till his retirement in 2001. He was by then 92 years outdated. “I’ve survived all of them,” he mentioned of the Nazis he’d spent half a century chasing. “If there have been any left, they’d be too outdated and weak to face trial as we speak. My work is completed.”

© 2022 All Rights Reserved. Don’t distribute or repurpose this work with out written permission from the copyright holder(s).

Printed from https://www.damninteresting.com/hunting-for-kobyla/

Because you loved our work sufficient to print it out, and browse it clear to the tip, would you contemplate donating a couple of {dollars} at https://www.damninteresting.com/donate ?